A road winds up into the hills above Palma. In the days when Joan Miró lived here, it was covered with nothing but the orange trees and the hot pink wildflowers that cover the Mallorcan countryside. Today, high-rise holiday flats and luxury villas interrupt the view out to the Mediterranean, but nestled amongst the modern construction sits a monument to the unspoilt calm that Miró found when he settled on the Spanish island in 1956.

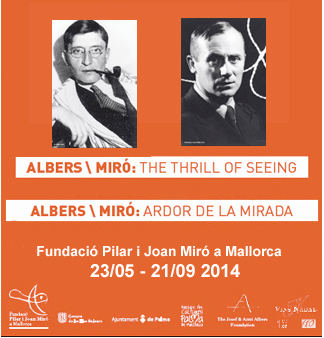

It is here, in the Miró foundation, that 11 unseen works by one of the great modernists of the 20th century have gone on show for the first time as part of new exhibition called The Thrill of Seeing. A group of sketches, colour studies, vast paintings and even metal printing palettes have been rediscovered in the archive and brought out of the museum cellars.

The works, says the foundation, will shed new light on the process Miró followed as an experimenting artist, offering new insight into how this giant of modern art thought through his own works. Sketches scribbled on torn paper enable viewers to see how some of his greatest works came into being. His palette, never before removed from the studio, hangs on the wall, blocks of blue, white and yellow paint preserved perfectly.

That process is further amplified by the juxtaposition in this exhibition of work by another artist, Josef Albers. The German-American painter, born in 1888, was rooted in geometry and rationality, almost diametrically opposed to Miró’s unrestrained style.

While the two painters never met, Nicholas Fox Weber, director of the Josef and Anni Albers foundation, came to Mallorca two years ago and was impressed by what he calls the “unspoken” similarities between the two seemingly contrasting artists.

“When I first came to the Miró foundation I was struck by the visual connections with Albers and I thought, well there’s no historical basis for it but I’m going to put his work next to Miró,” Fox Weber said. “I approached the director and she was spectacular in her enthusiasm and flexibility with which she has let me realise this project. People have this tendency to want to typecast artists in a very succinct way and the idea is to break both these artists out of that. This exhibition sets Miró’s paintings free.”

The Mallorca Miró foundation, which sits next to the house once lived in by the artist and still occupied by his grandson, houses more than 2,000 pieces donated by the artist in 1981, and complements the larger Miró collection in Barcelona. But while the most well-known works in the Mallorca collection are kept on the gallery walls, hundreds of drawings and prints are kept behind closed doors.

Works newly on show include a vast black and white painting that could easily be a part of his well-known monochrome series, as well as the metal plates that Miró used for his famous prints, which are works of art in themselves. One of the most personal works exhibited for the first time is a surrealist sketch of a family, drawn by Miró in 1974 on the back of a calender.

Fox Weber continued: “A lot of the smaller Mirós are not seen that frequently and a lot of the sketches have not been exhibited before because I retrieved them from the depths of the archives. This exhibition, by extracting them from this history and focusing on the process, on experimentation, has given these works a purpose not seen in exhibitions of Miró before. For once, you don’t have to discuss what the artwork is doing, it is just there to be enjoyed,” he said.

Miró’s grandson, who shares the artist’s name, praised the exhibition as “pure poetry”.

Fox Weber, who was a close friend of Josef Albers before he died in 1976, acknowledged that an exhibition, focusing not on art history or a certain time period within art but simply on visual similarities, could attract criticism but insisted that putting Miro and Albers, two seemingly unconnected artists, in tandem was about engaging a fun and freedom both artists utilised in their works.

He added: “You have artists making work and they are not thinking about themselves in a cannon, or categorising themselves. Albers and Miro are fascinated with connections, inter-relationships and sometimes purely maternal and sexual imagery so in my mind it makes perfect sense. These are two happy artists, it is as simple as that, and this exhibition is embracing that joy. By using Albers as a starting point it has enabled Miro, this artist we think we all know so well, to be seen in a different way. It has changed both of the artists, it has made the Albers gain some of that bursting energy of the Miro, while also drawing out the colours in the Miro. Both were very formal artists who liked letting go, loved accident, loved spontaneity and loved animating thing. I think putting them together makes you feel an even greater sense of energy.”

Elvira Camara Lopez, director of the Mallorca Miró foundation, said this was the first time works by Miró had been placed in such a context. “We have learnt a lot about Miró from this exhibition. We are so used to joining Miró to this organic idea, so to attach to this very structural artist, and see they had a very similar spirit and way of thinking it was wonderful,” she said.

“And to be able to bring out these works by Miró that have not been seen before from the archives, these very different works that still have a story and narrative, I am very proud to have done this in the exhibition and Nicholas is very proud as well.

She added: It’s something a bit unusual.

“I am hoping we can organise for it to travel to different countries, give people the opportunity to view Miró’s work in this new way, with this different story.”